In this post, I want to talk about synthetic polynomial division and why the final value you get is BOTH the value of the function at a particular point AND the remainder when you perform the division. We’ll use one running example with coefficients

, and even though our example will be with a cubic polynomial, the same idea generalizes to polynomials of any degree.

Let’s let , and lets let

. We want to compute

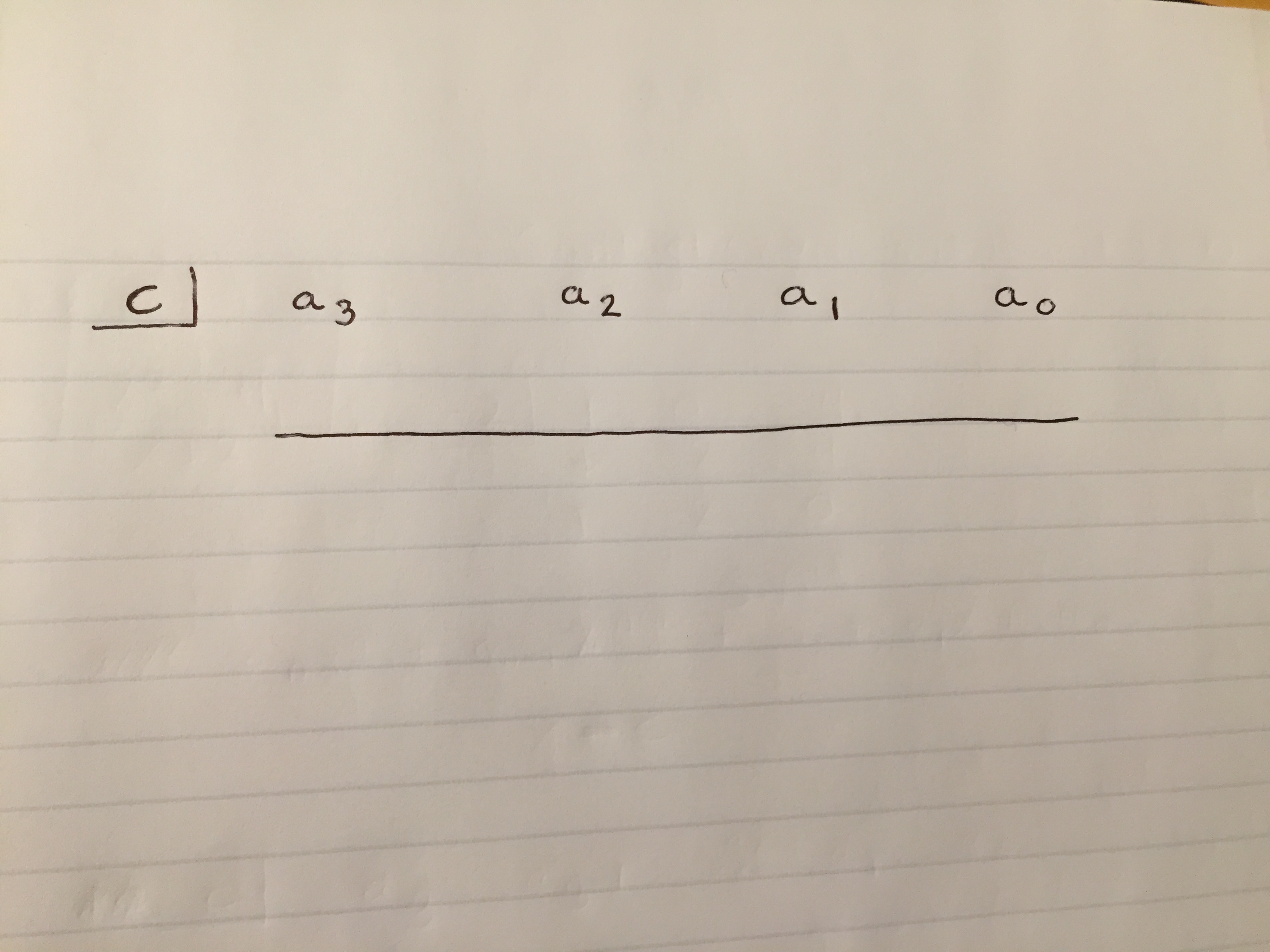

. To do this, we’ll set up synthetic divison as follows.

Inside the box, we put the value that makes the denominator zero. One of the assumptions of synthetic division is that the highest degree on the term is

. So, if

is inside the box, we know that we are dividing by

.

To the right of the box, we put the coefficients of the polynomial in question (in decreasing order of exponent). If there were a term missing as the powers decreased (like if the polynomial were (no

term)), we would put a zero in that position.

Now, let’s do some synthetic division. This is a combination of two steps: add and multiply. In the first step, we’ll just be bringing down the first constant, but that’s the same as adding zero to the first constant. Here’s the result if you carry out the synthetic division in this example.

The last term in the last column above the horizontal line that’s hard to read is .

The expression in last column of synthetic division below the blue line always gives the remainder of the polynomial division. However, we can ALSO see that this expression is the same as

, or the function

evaluated at

.

Hang on, that’s pretty cool. The remainder of the polynomial division by is the same as

value of the function at

.

Now let’s talk about why the final term being zero when plugging in corresponds to

being a factor of

. If

, then we can write

as a product of two polynomials,

, where

is some other polynomial (Note that if you evaluate

, you’ll get

).

Even if the term you’re dividing by is not a factor of , we see that synthetic division still gives you the $y-$value at that point. Thinking in terms of remainders, this also makes a lot of sense. The remainder after division can be thought of as a measure of how far the denominator was from being a factor of the numerator. If, at

, the

value of the function was

, then the numerator was

more than a multiple of the denominator. In other words, if you subtract

from the numerator, it will be divisible by the denominator with no remainder. And, this will have created a polynomial which IS a multiple of the denominator.

Let’s look at an example to make this a little more concrete. Let’s let , and let’s let

. Then, the synthetic division will look like this.

The final value in the bottom right is $7$, so this should be the $y-$value of the function at . We can check that

. Also, if the remainder is

, then we should be able to subtract

and obtain a multiple of

. Let’s see if that works.

. Indeed,

is a factor of that new polynomial!

I hope this helped you see a connection between zeros and factors of polynomials! And how the output of synthetic division relates to the numerator function’s value at a particular point!

Remember to post this on Facebook and tell your friends about it! Also, you can subscribe to posts so you can be the first to read the next one!